About

Anne Hirondelle was born in Vancouver, Washington, in 1944 and spent her childhood as a farm girl near Salem, Oregon. She received a BA in English from the University of Puget Sound (1966) and an MA in counseling from Stanford University (1967). Hirondelle moved to Seattle in 1967 and directed the University YWCA until 1972. She attended the School of Law at the University of Washington for a year before discovering and pursuing her true profession, first in the ceramics program at the Factory of Visual Arts in Seattle (1973-74), and later in the BFA program at the University of Washington (1974-76). Anne Hirondelle has lived and worked in Port Townsend, Washington, since 1977.

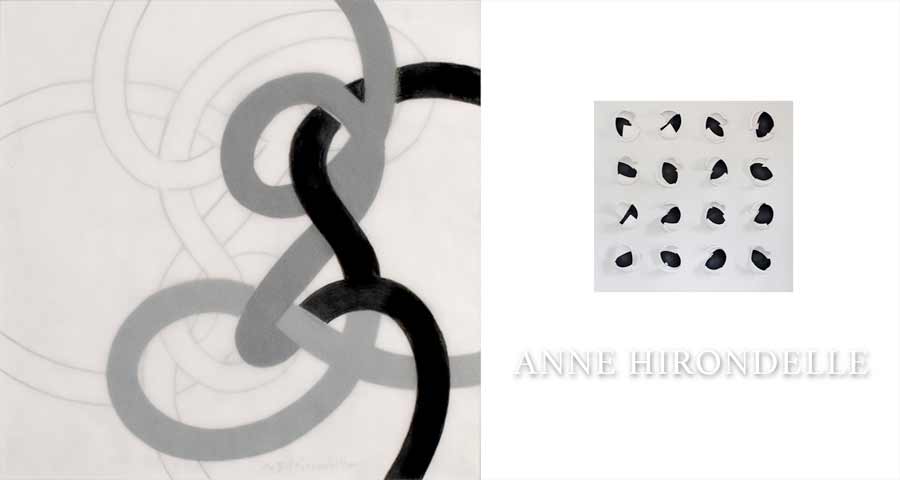

Hirondelle's beginnings as an artist were with clay. For over 20 years she was drawn to the vessel as an abstraction and metaphor for containment taking ideas from traditional functional pots and stretching them into architectural and organic sculptural forms. In 2002, to explore more formal ideas she abandoned her signature glazes for unglazed white stoneware and moved the work from the horizontal to the vertical plane. A year later she began painting the surfaces. Simultaneously, her drawings, once ancillary to the sculpture, took on a life of their own. Derived from the ceramic forms, drawn with graphite and colored pencil on multiple layers of tracing paper, they are further explorations of abstraction.

Hirondelle has exhibited nationally in one-person and group shows including: New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Kansas City, Scottsdale and Seattle. Her pieces are in myriad private and public collections including: The White House Collection in the Clinton Library, Little Rock, AR; The Museum of Arts and Design, NY; The L.A. County Art Museum and the Tacoma Art Museum.

She was the recipient of an NEA Fellowship for the Visual Arts in 1988. In 2004, Anne was a finalist for the Seattle Art Museum's Betty Bowen Award. In 2009 her accomplishments were recognized by the Northwest Arts Community with the Yvonne Twining Humber Award for Lifetime Artistic Achievement. The University of Washington Press published Anne Hirondelle: Ceramic Art, a book about her work in February, 2012. In 2014, she was one of four Washington State artists selected to participate in the Joan Mitchell Foundation's Creating a Living Legacy (CALL) Program.

Click HERE to download Anne's resumé.

Click HERE to download Anne's bibliography.

Click HERE to read an article on Anne in Numéro Cinq.

Essay by Kathleen Garrett, “Anne Hirondelle in the Layers.”

Anne Hirondelle in her studio.

Arts reporting by Carolyn Lewis

Step through the garden gate into Anne Hirondelle’s world, and it becomes immediately clear that her life is one of thoughtful arrangement and intentional beauty. A stroll around her lush, meticulously kept garden sets the tone—a prelude to the calm and quiet discipline that continues into her studio and home. Everywhere you look, there is a sense of order, of design, of care. Hirondelle refers to herself as an “arranger,” and the description couldn’t be more fitting.

Working vertically and layering translucent sheets, she draws with graphite and colored pencil, folding and re-folding the paper into precise configurations. The fragile material demands patience and attention. Its quiet, almost invisible lines reflect the kind of focused, meditative labor that seems to suit Hirondelle perfectly. “I’m always open to experimentation,” she says, and indeed, there are moments of unexpected play in the work.

A walk through her home is like stepping into a living gallery. Artwork from friends and fellow artists is carefully placed alongside her own. Everything feels like it has a reason. Her surroundings are not just beautiful—they are composed.

Late last year, her colorful piece, "Abouturn Grid," was purchased by Centrum in Port Townsend and can be viewed there. It is composed of eight wall-mounted forms in fired stoneware and paint. The Judith Reinhart Gallery in Seattle currently represents her and is hoping for a show in 2026.

Though her work has been exhibited nationally and is included in many museum collections, Hirondelle’s home studio feels like the heart of her creative life. There’s a quiet fulfillment in this space—a sense that this is where she’s meant to be, surrounded by calm, order, and the endless potential of form. If you should have the opportunity to visit Hirondelle yourself, you will be delighted by the beautiful surroundings, lovely conversation and a nice cup of tea.

View Hirondelle's work on her website at www.annehirondelle.com or swing by Centrum and see it in person.

Carolyn Lewis is a serial entrepreneur, artist, and community builder happily living and volunteering in Port Townsend. Visit her social media group on Facebook at Port Townsend Life and follow her on Instagram @linalewisart

ANNE HIRONDELLE

IN THE LAYERS

JUNE 17 - JULY 15, 2023

J. Rinehart Gallery

Click on the image below to view the catalog.

NOT DONE YET

Anne Hirondelle Retrospective

Jefferson Museum of Art & History, Port Townsend, WA

MARCH - JUNE 2020